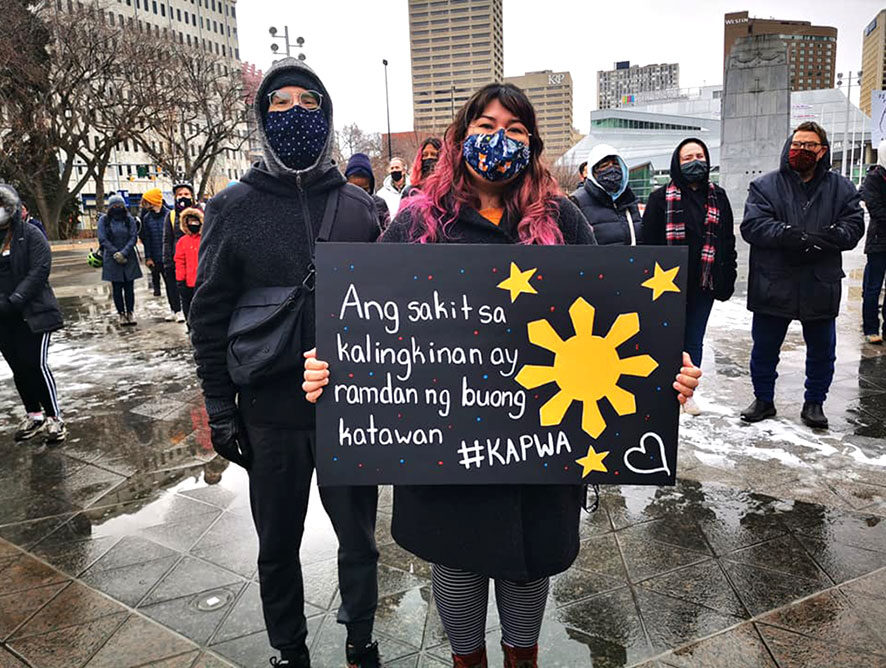

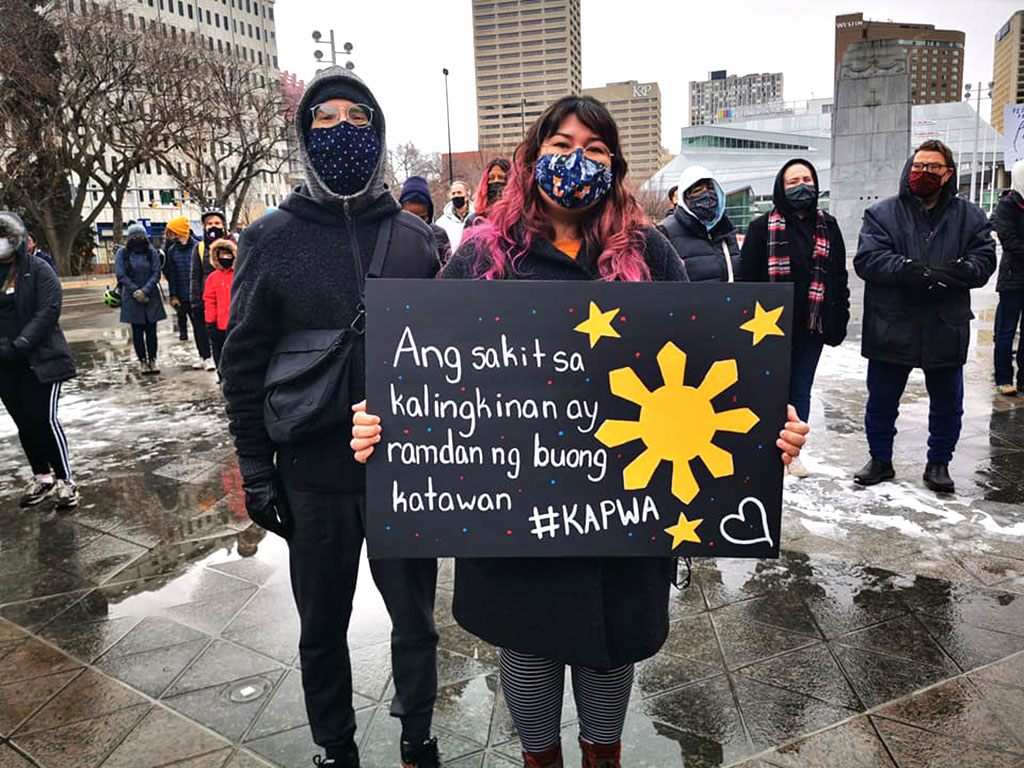

On March 27 a march and rally against Asian hate was held in Edmonton and Calgary. In Edmonton, there were about a hundred people that attended. The event was organized by Building Bridges Against Hate. The protest was held in light of the killings of eight people in Atlanta, Georgia, in the United States. Six of the eight people were Asian women. The killings sparked global grief and condemnations. Racism and violent attacks on Asians grew along with the spread of COVID-19 pandemic. In the US, former President Donald Trump’s first tweet about a “Chinese virus” triggered a rise in anti-Asian sentiments in the country. Trump called the virus “Wuhan Virus” or “Kung Flu”.

Here in Canada, there has also been a massive spike in violence. Global News reported that in Vancouver, the police documented a significant increase in anti-Asian hate crimes in 2020 – from 12 cases in 2019 to 98 cases last year. Last year alone, elimin8hate.orga website platform that provide an anonymous and safe reporting environment for Asians experiencing anti-Asian attacks reported that from March 10th, 2020 to February 28th, 2021 there were 1,150 cases of racist attacks across Canada. Another site called covidracism.ca reported 835 cases.

History of Racism against Asians in Canada

Covid-19 amplified not only the economic imbalance in our society but also anti-Asian racism. However, discrimination against people of Asian descent is not new. The Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion and the Canadian Council for Refugees put together a historical timeline of anti-Asian racism in Canada from the late 1800s.

• The Chinese Head Tax – this was part of the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885. A head tax was imposed on each immigrant entering into Canada. It started out as a $50 fee and increased to $500 by 1923. This created a significant financial burden to discourage Chinese from staying in Canada.

• Asians (Chinese, Japanese and South Asians) in West Coast BC were banned from voting in the Provincial elections between 1895 to 1908.

• In 1898, Asians were excluded from being hired in public works projects.

• In 1907, Asians were targeted to be checked for the bubonic plague that hit the Western US and Canada

• In 1908, the number of immigrants coming from Japan was limited to 400 per year, and then further reduced to 150. That same year, South Asians were accused of stealing “white jobs”. Anyone coming from India that was not part of the “Continuous Journey Regulation” was banned from entering Canada.

• In 1914, South Asian passengers from the ship Komagata Maru were prevented from entering Canada. They were held for two months at the dock in British Columbia and were sent back home to India where some were killed by Indian authorities upon arrival.

• In 1914 in Ontario, Saskatchewan and BC, legislation was created to prevent businesses owned by Asians from hiring white women. These laws were only repealed in 1968.

• During the Spanish Flu of 1918, Chinese patients were barred from a number of “white” hospitals in Montreal.

• The Public School Board in Victoria, B.C. voted in 1922 to segregate Chinese students, who were sent to Chinese-only schools.

• The Chinese Immigration Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act that was implemented between 1923 to 1947 banned Chinese people from immigrating to Canada. The Chinese community referred to the day it was implemented as “Humiliation Day”.

• At the beginning of the Second World War, over 22,000 Japanese Canadians living in B.C. were forced from their homes and sent to internment camps. The Canadian government confiscated and sold their property without consent. After the war ended, many were deported.

• The Immigration Act of 1952 provided powers to the Ministry of Immigration to admit and/or refuse on the grounds of nationality, ethnic group, geographical area of origin, peculiar customs, habits and modes of life.

• The Chinese Adjustment Statement Program of 1960 was announced. The program included measures to curtail “illegal” entry of Chinese and to land Chinese in Canada without legal status.

• In July 1999, a boat with 123 Chinese passengers arrived off the West Coast. They were met with hostility from the public. Most of the Chinese were kept in long-term detention and some were irregularly prevented from making refugee claims.

These are only some of the systemic racial discriminations against Asians in Canadian history. In 2003, during the height of the SARS or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (a viral respiratory illness similar to COVID-19), Asians were also under attack. There was similar racial panic, and over the spring of 2003, Torontonians boycotted the Chinese community, devastating Asian-owned small businesses. In some reports during that time, Asian-owned businesses lost up to 80 percent of their income. That stigmatized Asian Canadians.

The awkward silence of my community

While these often violent attacks against many Asians in the United States and Canada inspire many to act and fight back, my community, the Filipino community hardly does. Many continue to be silent. Even though my community prides itself on its culture and achievements on one hand, it has also created a culture of silence in times of crisis and the belief that fighting back and rebelling are shameful acts. Our deep colonial mindset insists on ideas such as “mag-tiis na lang, mawawala din yan (It’s just a little suffering, it will eventually disappear)”, “tumahimik na lang tayo at Diyos na bahala (Let’s just be quiet, God will take care of us)” and the famous “Wala ba kayong utang na loob (Don’t you have a debt of gratitude?)”. Our silence and complicity with regard to white supremacy is outstanding. It reflects our internalized colonialism and the model minority (model immigrant) myth.

At the anti-Asian hate rally there were a couple of young Filipinas. Perhaps this is a sign that this culture of silence will end soon. Young Filipinos and Filipinas need to break away from that colonial mentality. As a colonized people, we are used to making our colonizers happy and acting subservient. Our colonial history may shape our experiences and how we see ourselves and act even outside the Philippines. But that history does not define us. We define who we are, and we can take action. We can start by speaking up and being in solidarity with other oppressed peoples. That is how we stop being part of the problem.